Among all the battles in philosophy, one has been fought time and again across cultures and geographies. And yet, like everything else in philosophy, it remains unresolved. It’s the battle over the source of right knowledge. While metaphysics deals with what right knowledge is, epistemology concerns itself with the source of right knowledge.

In Western philosophy, the debate often centers on the superiority of reason versus the senses as the primary source of valid knowledge. Indian philosophy, however, goes further, outlining six distinct means (pramanas) through which one can attain prama, or right knowledge of reality. Interestingly, each school within Indian philosophy accepts only some of these six as valid, and this choice significantly shapes its metaphysical outlook. But before diving into the Indian perspective, let’s first explore some key views from the West.

Rationalism: The Mind’s Crystal Ball

On one side stand the Rationalists like Descartes, Spinoza, and Leibniz, who, to varying degrees, uphold the superiority of reason in understanding reality. They argue that optical illusions, dreams, and even basic misinterpretations of sensory input demonstrate that what we perceive isn’t always a true reflection of reality. A stick partly submerged in water appears bent, but reason tells us it is straight. In contrast, properly applied reason, especially through deductive logic, produces truths that are certain and indisputable.

Descartes gave his famous dictum: Cogito, Ergo Sum, that is, “I think therefore I am”, to define his existence as that of a “thinking” being.

According to rationalists, sensory experience only provides us with knowledge of particular instances, like a red apple. In contrast, reason can grasp universal and necessary truths, such as mathematical theorems and metaphysical principles (e.g., “nothing comes from nothing”). These truths apply across all times and places, independent of specific individual experience. Abstract ideas like “justice,” “beauty,” or even the concept of “being” itself comes from reason.

The human mind has an adequate knowledge of the eternal and infinite essence of God.

- Baruch Spinoza

Rationalists often strive to build comprehensive systems of knowledge, beginning with a few self-evident rational axioms and deducing further truths from them. They argue that even scientific knowledge, which relies heavily on observation, ultimately depends on rational principles for its coherence and justification. For instance, the principle of causality isn’t something that can be directly perceived, it can only be inferred.

“No fact can hold or be real, and no proposition can be true, unless there is a sufficient reason why it is so and not otherwise.”

- Leibniz

Rationalists argue that some innate or a priori knowledge is present in the mind from birth and can be known independently of sensory experience through intellectual intuition. While sensory experience might trigger our awareness of these innate truths, it doesn’t create them. For instance, seeing a physical triangle might prompt us to reflect on its properties, but the mathematical truths about triangles are grasped through reason, not perception. Some Rationalists believe that abstract concepts like ethics, beauty, and justice are also part of this innate knowledge.

Empiricism: Trust Your Senses

In direct opposition to Rationalism is Empiricism, which holds that all our knowledge ultimately originates from the five senses (sight, hearing, touch, taste, and smell) interacting with the external world. These sensory perceptions provide the raw data from which all ideas are formed. While sensation is central, many Empiricists (like Locke) also acknowledge “reflection” (thinking, believing, doubting, willing, and so on) as a source of ideas. However, even these internal experiences are built upon or shaped by prior sensory input.

To be is to be perceived

- George Berkeley

John Locke rejected the Rationalist notion of innate ideas through his theory of tabula rasa (blank slate). He believed that no concepts, principles, or truths are imprinted on the mind from birth. All ideas, whether simple (like “red” or “sweet”) or complex (like “justice” or “cause and effect”), are acquired through experience. He argued that if ideas were truly innate, they should be universally present and understood from birth, which is clearly not the case. For example, children and uneducated people don’t show knowledge of complex logical or metaphysical principles from the outset.

Empiricists contend that all factual knowledge is a posteriori, meaning it is gained after or from experience. We learn about the world by observing it, experimenting with it, and reflecting on those observations. But how do Rationalists know that their “clear and distinct ideas” or rational intuitions genuinely correspond to reality? According to Empiricists, Rationalism builds elaborate systems that may be internally coherent** but lack grounding in the real world. Without empirical checks, rational systems can become detached from reality. But empirical checks are based on sense experience which is unrealiable as per Rationalists.

Empiricists agree with Rationalists that sensory perception only provides knowledge of particular instances, but they believe that accumulating more and more of these instances leads to valid knowledge about reality. This is known as inductive reasoning, which forms the foundation of the scientific method, where hypotheses are formed based on observations and then tested through further experimentation and analysis. Knowledge, in this view, is built incrementally from accumulated evidence.

All our simple ideas in their first appearance are derived from simple impressions, which are correspondent to them, and which they exactly represent.

- David Hume

While Empiricists acknowledge the role of reason in organizing and processing sensory data, they are often skeptical of its ability to generate substantive knowledge about the world independently of experience. For radical Empiricists like David Hume, any idea or concept that cannot be traced back to a sensory impression is considered meaningless.

The Limits of Pure Reason and Raw Experience

It’s often said that the greatest strengths of both Empiricists and Rationalists lie in their critiques of the opposing view, while their own positive claims face significant challenges. Both schools encounter internal difficulties that are hard to resolve using only their foundational principles:

- Rationalists fail to defend themselves against the critique that they are building castles in the air, that is, they struggle to prove that what is rationally self-evident in the mind actually corresponds to objective reality, especially given their skepticism toward the senses. It’s difficult for them to demonstrate that their “clear and distinct” ideas (or innate knowledge) have any real connection to how the external world functions, or even that such a world exists at all.

- Empiricists, on the other hand, cannot easily answer the criticism that if all knowledge comes from experience, then why do some truths appear universally and necessarily true, without requiring validation through experience? For example, why is it that “a triangle always has three sides,” or that “2 + 2 will always equal 4”? Our experience might illustrate such truths, but it doesn’t seem to create them. Empiricism also struggles to justify our belief in inductive inferences about the future. Just because the sun has risen every day in the past doesn’t logically guarantee that it will rise tomorrow.

Leibniz took Rationalism to its extreme and arrived at a dogmatic theory of reality. David Hume, in taking Empiricism to its extreme, ended up with a skeptical view of reality. In fact, Hume even denied the validity of science, which, as Kant put it, “woke him up from his slumber.” The Carvakas in Indian philosophy were also Empiricists who accepted only perception (Pratyaksha Pramana) as a valid source of right knowledge, and they ended up denying the principle of causality, since we cannot perceive this principle.

Kant’s Middle Way: When Sense Meets Reason

Kant believed that both Empiricists and Rationalists are correct in what they affirm but wrong in what they deny. Rationalists claim that reason yields universal and necessary knowledge, but Kant argues that knowledge derived solely from reason lacks novelty, as it is merely drawn from self-evident axioms (e.g., a triangle has three angles, so it has three sides). Likewise, while sense experience provides new information, it does not offer knowledge that is universal and necessary. For Kant, true knowledge must be new, necessary, and universal.

Percepts without concepts are blind, and concepts without percepts are empty.

- Immanuel Kant

Kant gave his theory of knowledge formation, called Transcendentalism. According to Kant, we first receive discrete raw sensations from sense experience. These are unorganized and unassimilated inputs. For example, when we see an apple, we receive sensations of red, roundness, size, etc., but our mind doesn’t yet recognize it as an apple yet. These discrete raw sensations are then organized, ordered, and synthesized by the mind into proper knowledge, that is, the object is now understood as a red apple.

The mind is passive when receiving the raw sensations but becomes active when assimilating them into coherent understanding. Therefore, knowledge is formed by both sense experience and reason. While the senses provide the raw material for knowledge, the mind gives that raw material its form, meaning that raw input is molded into meaningful understanding by reason.

Nyāya’s Timeless Take: Two Steps, One Unified Perception

While Kant proposed this theory in the 18th century, a similar idea had already been presented by the Nyaya school in Indian philosophy at least 2000 years earlier. Nyaya also holds that perception has two stages: Nirvikalpa and Savikalpa perception. Nirvikalpa perception is the stage where the mind receives raw inputs from the environment. In the subsequent stage which is Savikalpa perception, the mind organizes these inputs into something meaningful. What’s interesting is that Nyaya explicitly states that these two stages differ only in theory, not in practice, that is, perception is an organic unity for all practical purposes, but it can be theoretically understood as a two-step process. According to Nyaya, our consciousness isn’t structured in layers where each layer activates only after the previous one completes its task.

The Staircase Fallacy and Why It Matters

Now, why does it matter whether these two steps exist separately or as part of one organic unity? To understand why, let’s consider the staircase fallacy:

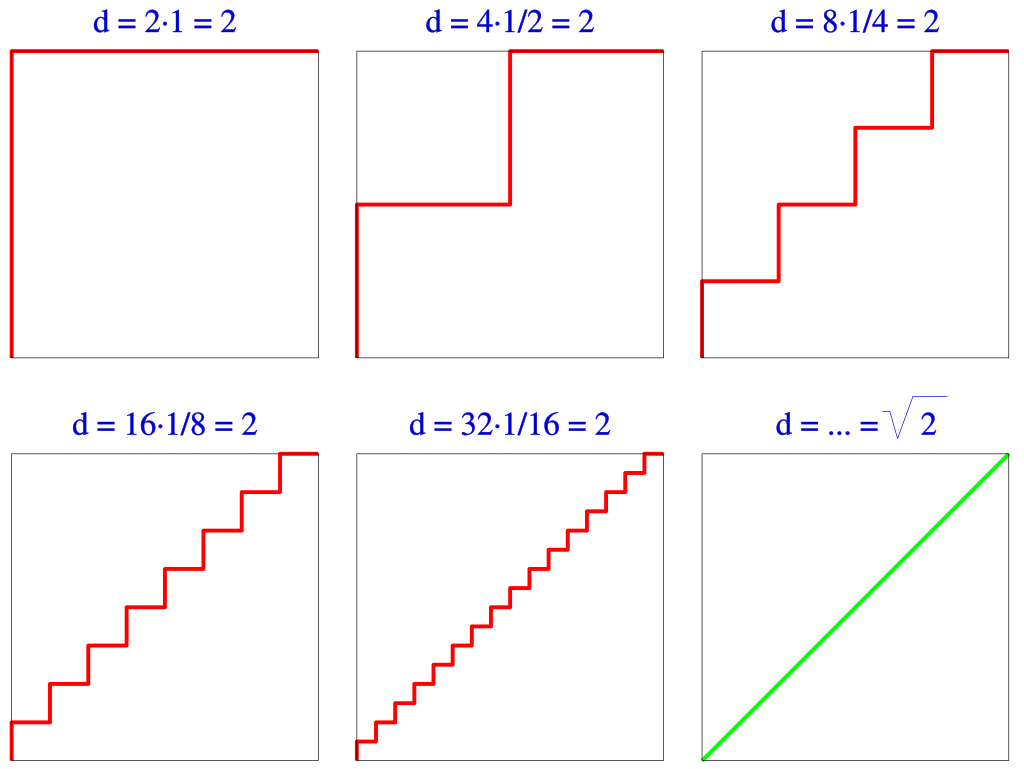

Imagine a unit square. In the first figure, the only way for an ant to get from the bottom-left corner to the top-right corner is by first climbing up to the top-left corner and then moving right (shown by red lines). This means the ant travels a total distance of 2 units.

In figures 2-5, we can see that even if we break the square’s left and top edges into multiple smaller segments, the ant still travels the same total distance by moving over these “stairs.”

But if we continue dividing these edges into infinitely many smaller segments, the steps start to merge into a smooth slope, and the path is no longer a staircase (last figure). In this case, the distance the ant travels is simply the diagonal of the square, which is not 2 units but √2 units.

This example shows why understanding a path as composed of discrete steps is fundamentally different from considering the path as a unified whole with steps embedded within it. So, when Kant describes perception as two stages but insists they exist separately even at the practical level, he commits what we might call the “psychical staircase fallacy.”

In contrast, Nyaya avoids this by treating the steps as embedded within a single unified process, not distinct in any practical sense. Nyaya even argues that any attempt to distinguish Nirvikalpa from Savikalpa perception is futile because the moment we try to perceive an apple as just raw sensations, we inevitably recognize it as a coherent object.

But who’s right? We can hold our opinions, but there’s no definitive proof for either view. Maybe someday we’ll settle these debates. But who knows if these things are even truly knowable? After all, we are using our mind to understand our mind. No matter how smart and complex it is, it’s trying to comprehend something just as smart and complex as itself. Can an ant understand its own mind using its own mind?

Thanks for reading!