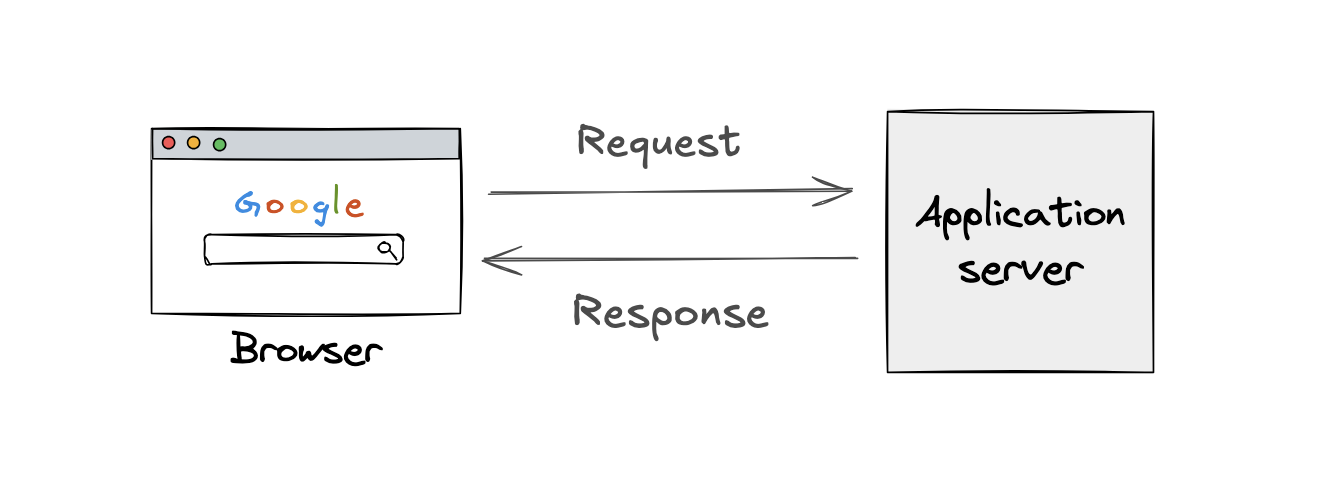

In the last few posts, we explored HTTP and the client-server model that underpins most communication over the internet.

In the traditional HTTP based client-server model, every interaction beings with the client: it asks for something and the server serves its request. Thus, a response from server has to be preceeded by a request from the client. This model works well for a lot of systems but can all modern systems rely on it? Think of WhatsApp: Can we build real time chat experience using just this request-response pattern?

Not really. In a chat application, you require the servers to push messages to your device the moment they arrive, without yout device constantly having to ask, “Any new messages?”. This is exactly how the traditional HTTP request-response model starts to break down for real-time use cases: real time dashboards, streaming apps, instant notifications, collaborative editing tools - they all need something more. Let’s dive into some communication protocols that help us build these systems.

Short Polling and Long Polling: The Early Hacks

Before we design something new, it’s natural to push the existing tools to their limits. In many cases, these creative “hacks” get us part of the way there. And while more elegant solutions eventually emerge, the old tricks often stick around because they’re simple, easy to implement, and easy to reason about.

One of the earliest hacks for enabling real-time communication was Short Polling. In this approach, the client repeatedly asks the server, “Got anything new?” If the server has new data for the client, it sends it back; otherwise, it replies with an empty response. This is a bit like refreshing a webpage over and over to check for new updates.

While short polling gets you close to real-time, it has some obvious drawbacks. Many of those repeated requests return nothing, which wastes bandwidth and increases load on the server. Plus, with a fixed interval between polls, you’re always a step behind the actual moment when the data is available, so it’s not truly real-time.

The natural next step? Ask the server to respond only when it has new data for the client. That’s where Long Polling comes in. In long polling, the client still initiates the request, but the server doesn’t respond immediately. Instead:

- It first checks if it has any new data for the client. If it does, it sends it right away

- If not, it holds the connection open for a short while (say, T seconds), waiting for any updates to arrive. If nothing comes in that window, the server finally responds with an empty result

While this does cut down on unnecessary requests from the client and empty responses from the server, it does have its diadvantages: the client gets only one response per request, so it still needs to start a new request for every new message. It’s closer to real-time, but not there yet.

📝 Note: Long polling is still used under the hood by some frameworks as a fallback mechanism. For example, libraries like Socket.IO fall back to long polling if WebSockets aren’t supported by the client or network.

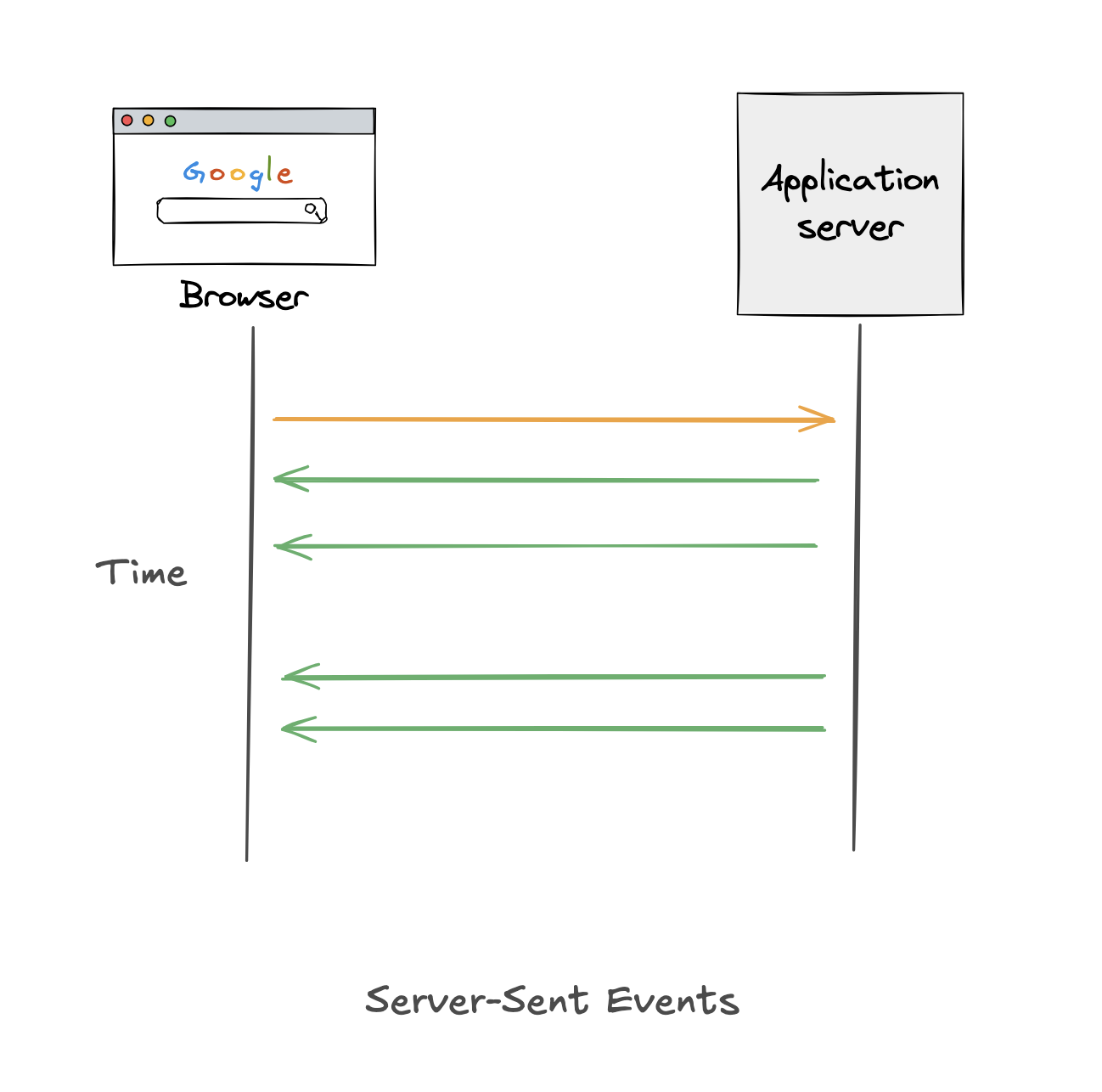

Server-Sent Events (SSE): One-Way Real-Time Streaming

Server-sent Events make it possible for the server to push messages to the client without the client having to constantly ask for them. These messages, known as “Events”, are initiated by the server and sent to the client over a single long-lived HTTP connection. Only the server can send events to the client, making SSE a unidirectional channel of communication.

On the client side, the EventSource API is used to open this persistent connection. Unlike a normal HTTP request, the connection doesn’t close after one response but stays open, allowing the server to send new messages to the client as and when they become available. In the first response from the server, the server must set the Content-Type header to Content-Type: text/event-stream and Connection to Connection: keep-alive to keep the connection open. This tells the client that the content being sent is a stream of events, not a one-time payload. The client uses EventSource interface to listen for events from the server. After the initial response from the server, the rest of the communication is a plain-text stream of event data (no HTTP headers from now).

Each event in a stream is a block of UTF-8 encoded text. Each message consists of one or more lines of text, separated by \n\n, and each line follows the format field_name: field_value_as_string. The SSE protocol supports four fields:

event: the name/type of the eventdata: the actual content of the message. If there are multipledata:lines in a single event, the EventSource API on the client side joins them with newline charactersid: a unique ID for the event; useful for reconnecting and resuming from where the stream left offretry: tells the client how long to wait (in milliseconds) before attempting to reconnect if the connection drops

Out of these, the data field is required, and rest all fields are optional. If a message beings with a colon, the EventSource API treats it like a comment and ignores it. This feature is often used by the server to send hearbeat or keep-alive messages to keep the connection alive. A typical keep-alive might look like:

: keep-alive\n\n

SSE is especially useful in applications where data needs to flow only from the server to the client, like live stock price feeds, live sports scores, app monitoring dashboards, news feeds, or push notifications. It’s lightweight, works over standard HTTP/1.1, and is easy to implement as long the client’s device or browser supports it. Unlike WebSockets, SSE doesn’t require a special upgrade handshake. This makes it firewall and proxy friendly.

One thing worth noting: SSE doesn’t support binary payloads, so it’s not ideal for streaming large or complex data formats. For use cases like that, WebSockets might be a better fit.

📝 Note: While SSE works well over

HTTP/1.1, it doesn’t play nicely withHTTP/2due to its multiplexing behavior, which can interfere with the real-time delivery of event streams. As forHTTP/3, it’s built on QUIC (which uses UDP), whereas SSE relies on a single, ordered, long-lived TCP connection. For now, sticking withHTTP/1.1remains the most reliable choice for SSE.

Practical Considerations for SSE

- Scaling: If you’re running multiple server instances, an event intended for multiple clients might not reach them if they’re connected to a different instances. To solve this, tools like Redis Pub/Sub, Kafka, or message queues are commonly used to fan out events across servers

- Reconnection & Event IDs: SSE includes built-in automatic reconnection, and the

id:field helps clients resume from the last message they received. But this means your server needs to support replay or caching if you want robust reliability across reconnections - Proxy and Load Balancer Timeouts: Since SSE connections stay open for a long time, reverse proxies (like Nginx) and load balancers might mistakenly think they’re idle and close them. To prevent this, servers often send lightweight heartbeat messages like

: keep-alive\n\nto keep the connection active

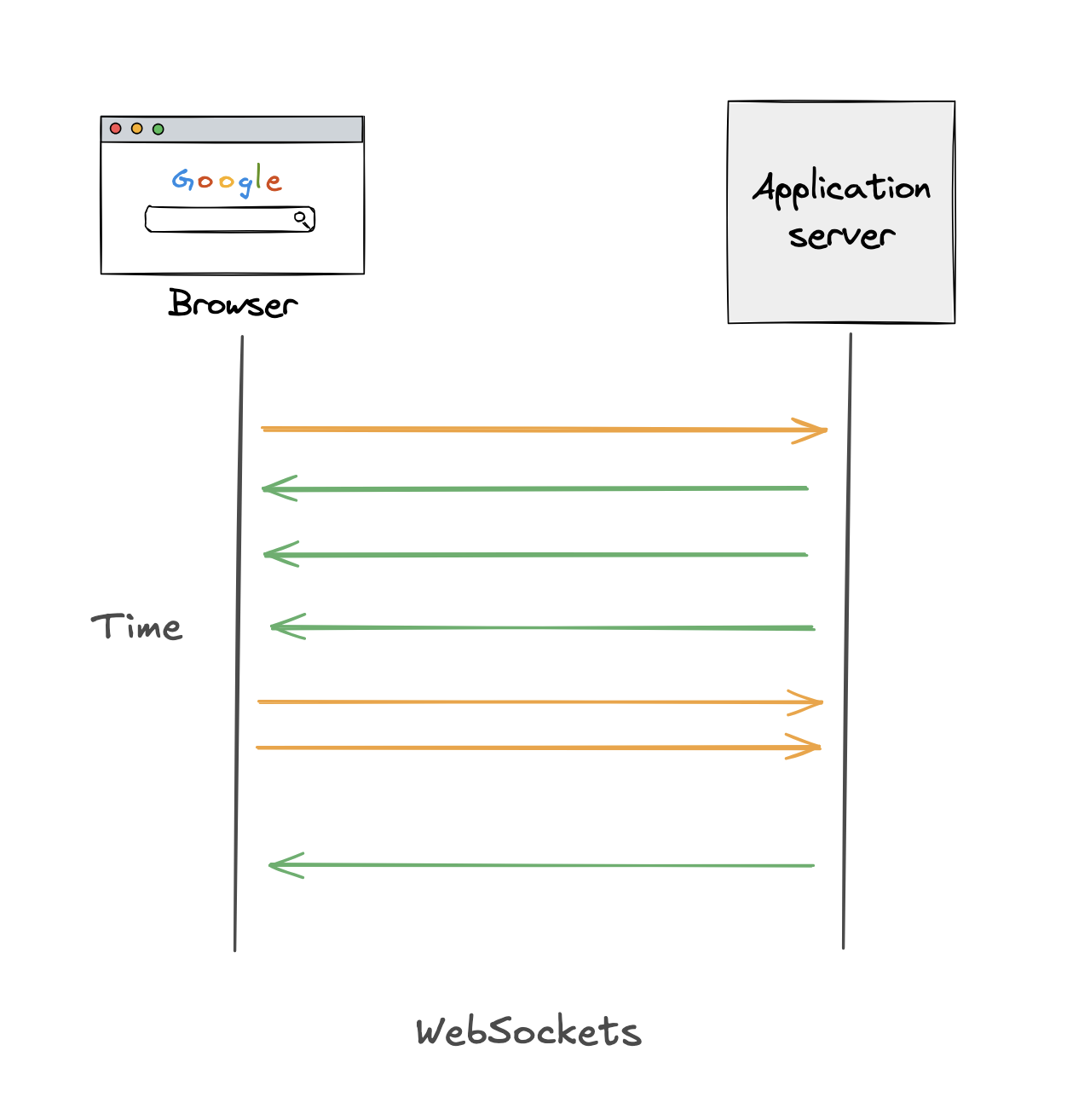

WebSockets: Full-Duplex, Persistent Communication

WebSocket is a communication protocol that enables a bidirectional, full-duplex channel between the client and server over a single persistent TCP connection. Unlike HTTP, which follows a request-response model and is inherently half-duplex, WebSockets allow both the client and the server to send messages independently at any time. This makes WebSocket ideal for real-time applications.

The connection starts with a standard HTTP request, but with a twist: the client includes a special Upgrade header to request switching to the WebSocket protocol:

GET /chat HTTP/1.1

Host: server.example.com

Upgrade: websocket

Connection: Upgrade

If the server supports WebSocket, it responds with 101 Switching Protocols:

HTTP/1.1 101 Switching Protocols

Upgrade: websocket

Connection: Upgrade

This is known as a HTTP handshake. After this point (once TCP and HTTP handshakes are done), the protocol is upgraded from HTTP to WebSocket over the same TCP connection. At this point, both the client and server can exchange messages freely, without having to reestablish a connection for each one.

Instead of HTTP messages, data is now sent as WebSocket frames - a compact binary format optimized for performance. These frames are structured with a small header and a payload. Some key details:

- The header contains metadata like whether it’s the final frame in a message, the message type (binary, ping/pong, close), and payload length

- Large messages are often broken into multiple frames, with flags indicating if more frames are coming or not

- Clients are required to mask the payload for security (essentially encoding it), and the server must unmask it before reading

WebSocket communication remains open as long as needed. The TCP layer guarantees frame delivery and ensures that the frames arrive in order. The client and ths server can send ping/pong frames at the WebSocket level to check if the connection is alive. To close the connection gracefully, one side sends a close frame, followed by a standard TCP four-way termination handshake.

WebSockets are a go-to choice for use cases that need real-time updates or low-latency bidirectional communication, such as chat apps, multiplayer games, collaborative editors, live stock/crypto feeds, and notification systems.

Secure WebSocket connections use the wss:// scheme, much like how secure HTTP uses https://. This ensures that the WebSocket traffic is encrypted using TLS, protecting it from eavesdropping and tampering. WebSockets are widely supported across modern browsers and environments. Libraries like Socket.IO often fall back to long polling or SSE when WebSockets aren’t available, for example, due to restrictive firewalls or proxy settings.

Practical Considerations for WebSockets

- Scaling: Each user maintains an open connection with the server. So if you have a million users, your backend must be able to handle a million concurrent WebSocket connections. In distributed systems, users may be connected to different application servers, meaning one user might send a message to another who’s connected elsewhere. To handle this, tools like Redis Pub/Sub or message queues (like Kafka or RabbitMQ) are often used to broadcast messages across servers

- Load Balancing: WebSockets require careful load balancing. Since the connection is long-lived, it’s common to use sticky sessions to ensure a user consistently connects to the same server. This reduces the complexity for your message routing layer, especially if you’re keeping track of which users are connected to which servers

- Connection Limits: If a user sends too many messages too quickly, it can overload the server. To prevent abuse and maintain system stability, implement rate limits, timeouts, and possibly authentication checks to manage usage patterns and protect resources

Protocol Comparison

| Feature | Short Polling | Long Polling | SSE | WebSockets |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direction | C ➝ S | C ➝ S (wait) | S ➝ C | C ⇄ S |

| Full-Duplex | ✘ | ✘ | ✘ | ✔️ |

| Binary Support | ✘ | ✘ | ✘ | ✔️ |

| Complexity | Low | Low-Medium | Medium | High |

The best way to really understand these protocols is to implement them yourself. If you’re curious, this walks through Python implementations of short/long polling and SSE, and this one covers how to build a WebSocket server in Python.

Real-time on the web isn’t magic, it’s just clever protocols and good infrastructure. Hope this helped clear the fog. Happy building!