Of all the schools of Indian philosophy, Jainism stands apart in some really interesting ways. In a world where we’re constantly chasing certainty and clear answers, Jainism flips the question and asks - What if everyone’s right?

To understand the depth of this perspective, let’s rewind 2500 years to a time when thinkers in both India and Greece, were wrestling with the same question: the nature of reality. On one side, the Vedanta school of philosophy asserted that the ultimate reality must be unchanging and untouched by time. Thus, any change that we perceive is mithya - not exactly false, but an illusion (a crude translation). The ultimate reality itself is eternal and unalterable. On the other hand, Buddhism took the almost opposite view - everything in the world arises, changes, and passes away. Thus, change is the only constant in the world i.e. impermanance is the only reality. Clinging to anything permanent is like trying to hold on to smoke.

In Greece, Heraclitus (whose views echo Buddhism) famously said: “You cannot step into the same river twice”. He saw reality as an ever changing flowing process. What looks stable to us is, in his view, just a temporary illusion, and everything is in motion, all the time. While Heraclitus embraces becoming, Parmenides (strikingly similar to Vedanta) insists on being. For something to change, it must stop being what it is and start being something else. In this state of transition from one state to another, that thing enters the state of non-being (even if for a moment) and that is a logical impossibility. Thus, Parmenides rejected all movement and change and argued that reality is eternal, indivisible, and unchanging and it is only our senses that deceive us into thinking otherwise.

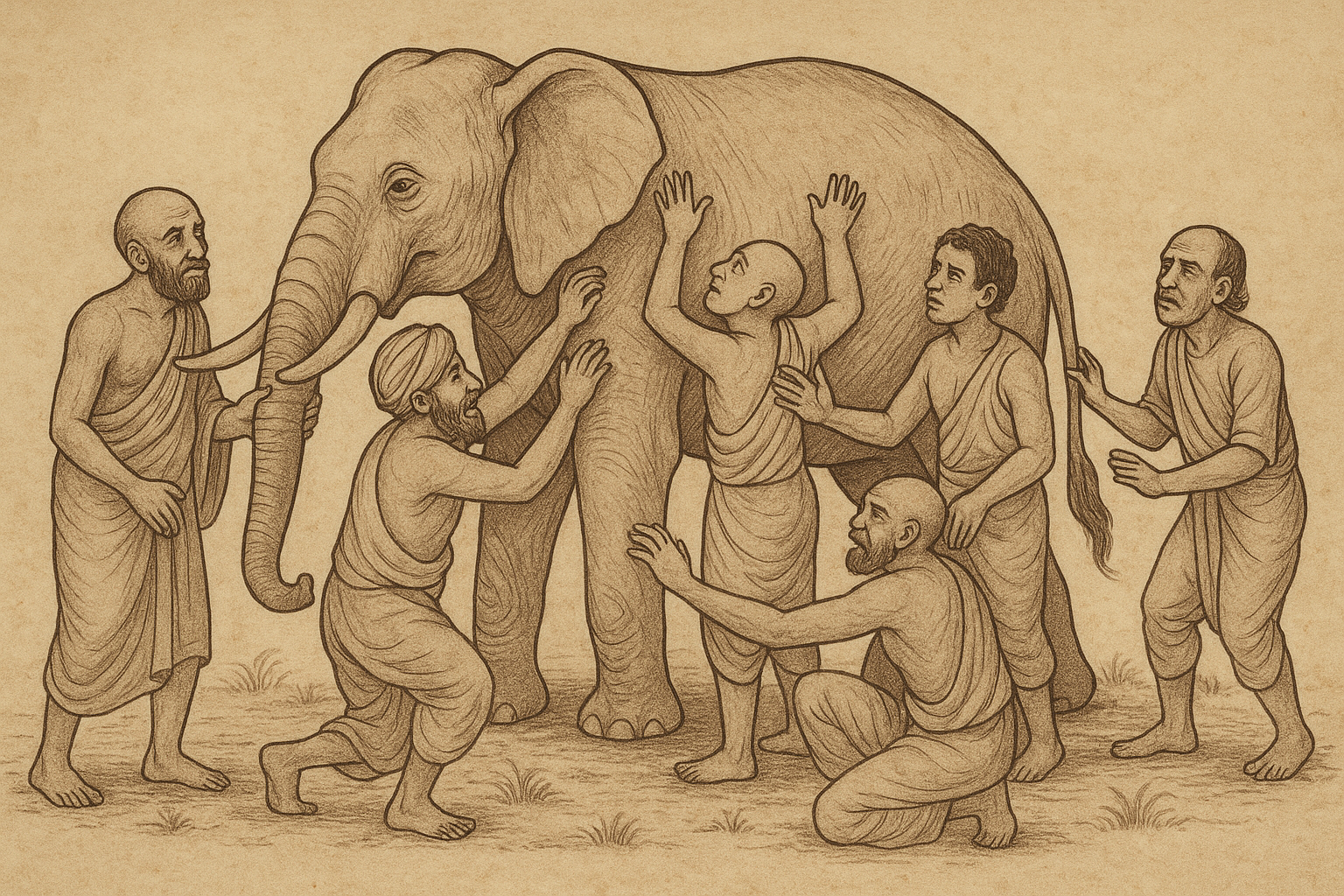

To understand how Jainism sees ultimate reality, there’s a classic story that captures it beautifully - the one about the six blind men and the elephant. Each of the men encounters the elephant for the first time, but since they can’t see it, they each touch a different part of the elephant to understand what it is. They all reach very different conclusions. One grabs the trunk and confidently declares it’s a snake. Another feels the leg and insists it’s a pillar. A third touches the tail and says it’s obviously a rope. Each person is convinced they’ve figured out the whole truth, but of course, they’re all only partly right.

Jainism sees human attempts to understand reality as not so different from those blind men trying to make sense of the elephant. Reality, according to Jain thought, is immensely complex and multifaceted, with infinite aspects and dimensions. Any statement or judgement (Naya) made by us about reality is always shaped by where we’re standing: our context, our moment in time, and our limited point of view. Our cognitive capacities are finite and our perception is limited. Thus, we can’t see reality as it truly is but only as it appears to us through the lens we use to understand it. This idea, that knowledge is always partial and bound by perspective, is what we now call epistemological relativism.

But Jainism doesn’t stop at just perception. It also holds a detailed metaphysical view of reality itself. The universe, it says, is made up of infinite individual souls (jivas) and infinite material atoms (pudgala), all separately and independently real (a strong form of realism and pluralism). And each of these entities has an infinite number of characteristics or modes.

All of these come together in Jainism’s theory of manyness of reality, Anekantavada - the doctorine (vada) of many (aneka) aspects (anta).

Jaina philosophy is often described as realistic and relativistic pluralism. That’s a mouthful, but it captures the two key threads of their thought. On the metaphysical side, there’s Anekantavada, the idea that reality itself has infinite aspects to it. On the epistemological side, there’s Nayavada, the theory that all human knowledge comes from partial perspectives. In this view, all human knowledge and understanding is and will always be limited (by our senses and cognitive capacities), conditioned (by our standpoint), and relative (to our point of view). Jainism uses the term naya to refer both to our point of view and to the statement or judgement we make from that point of view.

Where other philosophical schools often commit to a single viewpoint, a position Jainism critiques as Ekantavada (one-sidedness), Jainism argues that this leads to incomplete and inadequate understandings of reality. No single view, however well-reasoned, can capture the full picture. For Jain thinkers, every perspective contains some truth and no perspective holds the whole truth. This promotes intellectual humility, philosophical tolerance, and the idea that multiple viewpoints can coexist without contradiction.

According to Jainism, there are three ways we can talk about reality, but only one of them is valid:

- If we make absolute claims, like, “This pen absolutely exists”, we’re making what Jainism calls a false or invalid judgement (Durniti)

- If we drop the absolutism, but still make statements without acknowledging our point of view, like, “This pen exists”, they are still invalid (Naya)

- If we qualify our statement with Syat (which means “Relatively Speaking”), like, “Syat, this pen exists”, our statements become valid as now we’ve acknowledged that our statement is true, but only from a specific point of view.

When we speak this way, our partial perspective (naya) becomes a valid expression of knowledge (pramana). This is Syadvada, the Jain method of speaking truthfully in a world that’s always more complex than any one perspective can capture.

So, coming back to the question we began with: Can you step in the same river twice? Jainism offers a quietly profound answer in a single line:

Utpadavyaya dhrauvyam samyuktam sat

Utpada: Origination

Vyaya: Decay

Dhrauvyam: Permanence

Samyuktam: Combination

Sat: Reality

This phrase translates into: “That which is a combination of origination, destruction, and permanence is real (sat)”.

According to Jain philosophy, nothing that truly exists is completely static or completely fluid. Instead, change and permanence coexist in everything. Every object or being has certain essential qualities, called gunas, that remain stable and other accidental attributes, called paryayas, that constantly change. A few examples help make this clear:

- For a soul, consciousness is its guna, its eternal defining essence. But experience of pleasure and pain are paryayas. The soul passes through many emotional states, but its core capacity for awareness never disappears

- For a clay pot, the clay itself is its guna while its shape is its paryaya. Over time, the pot may break or crack, but despite these changes, there is a substance (clay) that underlies and persists

So when someone claims that reality is constantly changing, Jain thinkers would say: they’re looking at the changing modes of reality, the paryayas. And when someone insists that reality is unchanging and eternal, Jainism replies: they’re focusing on the essential qualities, the gunas. Both of these views contain truth, but they’re partial truths. Each is a product of Ekantavada, a one-sided view that clings to a single aspect (ekanta) of a much more complex reality.

From the Jain perspective, the problem isn’t that these statements are wrong, but that that they’re incomplete. This is where the word Syat becomes essential. As per Jainism, both should be preceded by Syat for them to be taken as pramana (valid knowledge). According to Jainism, the complete truth reveals itself when we look at reality from different perspectives.

It’s important not to confuse this with agnosticism or skepticism. Jainism isn’t saying that we can’t know anything with certainity. Instead, it’s saying: truth is real, but it’s always relative to perspective. Knowledge isn’t impossible - it’s just never total or absolute from a single point of view.

If you’re feeling a bit uneasy or skeptical about this philosophy, don’t worry - you’re not alone. This philosophy has been criticised by its contemporary schools as well. One of the most famous critiques of all relativistic philosophies is that relativism can’t sustain without an absolute i.e. it is an absolute only at the end that is merely perceived or expressed differently through the different lenses viewing it.

Maybe truth is less about stepping in the same river twice and more about enjoying the splash every single time.

Thanks for reading - don’t forget to add a little Syat to your day!