Imagine you’re streaming your favorite show on Netflix, hopping on a video call with teammates across time zones, or just sending a quick message to a friend. Behind each of these simple actions, your device is taking part in a very real and highly structured conversation with other machines scattered across the globe. This invisible dialogue is made possible by the magic of computer networks.

Networking is a foundational part of any system you’ll build as a developer. At its core, a network is just a medium that allows independent machines to exchange information. But how do these machines agree on how to talk? How do messages go to the right place? What happens if something goes wrong along the way?

In this post, we’ll peel back the curtain and demystify how computers communicate. While computer networking is a vast field, this blog (and others I’ll share) will focus on the just the very essential concepts every software developer should understand.

Networking layers

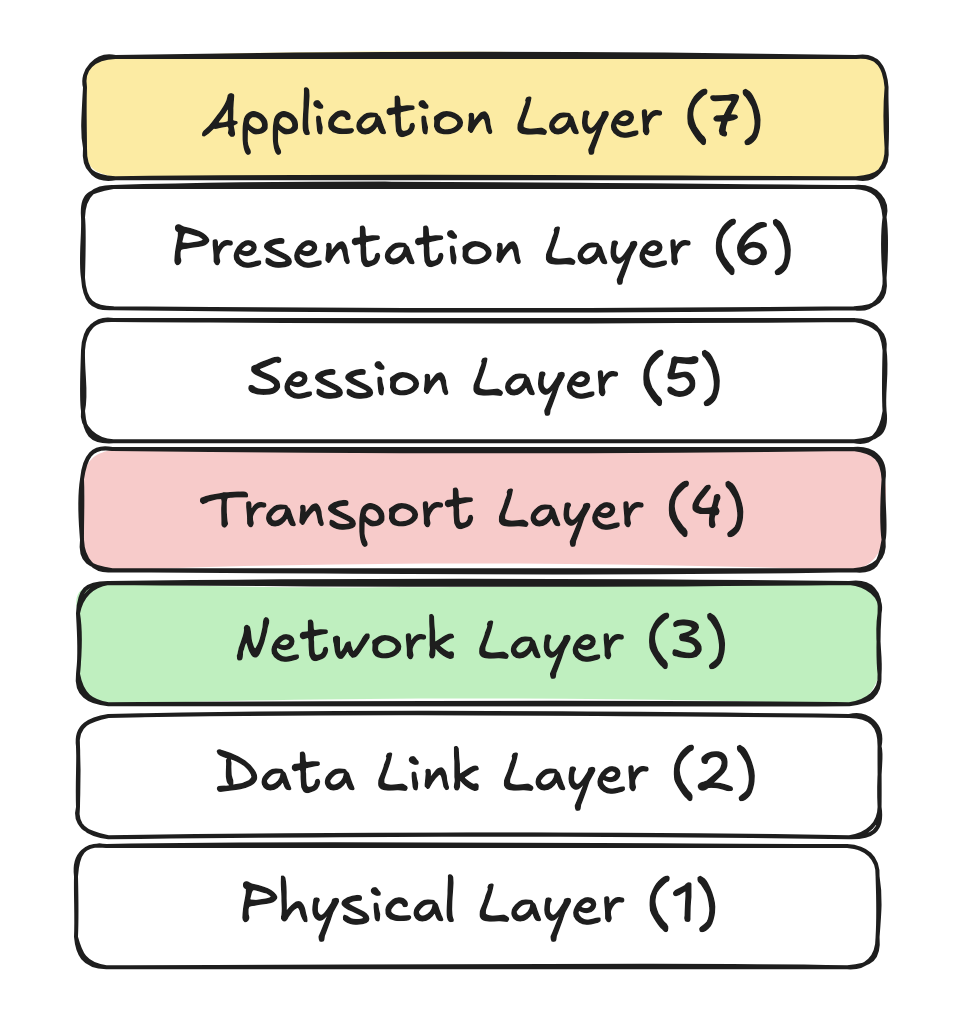

When we talk about how data moves across the internet, from your laptop to a server across the globe, it helps to think in layers. The OSI Model (Open Systems Interconnection Model) gives us a layered view of this journey. It is a conceptual framework that breaks the communication process into seven layers, each having a specific role in network communication. When your computer sends data, whether it’s a chat message, a video stream, or a web page, it doesn’t just shoot that data across the internet in one go. Instead, it follows a carefully structured journey through the layers of the OSI model.

|

|---|

| OSI Model |

Each layer in the OSI model relies on the services of the layer below it while providing services to the layer above it. On the sender’s side, the message travels down the OSI stack. At each layer, additional information (called headers) is added, a process known as encapsulation. These headers contain the instructions needed to ensure the message can be properly delivered across the network. On the receiver’s side, the message flows up the OSI stack. Each layer reads and removes its corresponding header, a process known as decapsulation, revealing the original data, step by step.

Each layer on one machine logically “speaks” directly to its corresponding (peer) layer on the other machine – even though in reality, data travels down through the OSI layers on the sender’s side and up through the layers on the receiver’s side. This conceptual exchange is known as layer-to-layer communication.

How does the OSI model help?

- Standardization: OSI model standardizes the communication process ensuring that devices from different vendors and platforms can communicate with each other seamlessly

- Learning tool: The OSI model’s layered structure makes it an excellent way to understand how data moves through a network. By breaking the process into distinct, manageable layers, it allows us to study one piece at a time, making the complex world of network communication more digestible

While the OSI model has seven layers, most developers arguably only need to focus on three key ones: Layer 3 (Network), Layer 4 (Transport), and Layer 7 (Application). But let’s zoom out briefly to see what each layer does:

- Application layer Block (Layers 5-7 combined): Although the OSI model defines three separate layers at the top (Application, Presentation, and Session), in real world use, we usually treat them as a single block: the Application Layer. This is where the magic starts – where users interact with software like web browsers, Zoom, or email apps. Think of it as the front door to network communication – everything else supports what happens here.

- Transport Layer (Layer 4): This layer is responsible for ensuring reliable and/or fast data transmission and splitting data into chunks (called segments). Analogy: Imagine trying to send a book through the mail, but all you have are small envelopes. So, you tear out each page, place it in an envelope, and number them. The Transport Layer does exactly this – it splits your data into parts, labels them, and keeps track of what was sent and received.

- Network Layer (Layer 3): Here’s where the addressing and navigation happens. This layer decides where data goes and plots the best route to get there (routing). It uses IP addresses, much like street addresses, to make sure your data reaches the right destination, whether that’s across the room or across the ocean. Analogy: You’ve addressed your envelopes with the recipient’s house number and ZIP code and the postal system has figure out the fastest, most efficient delivery route.

- Data Link Layer (Layer 2): This layer takes care of communication within a local neighborhood i.e. between devices on the same network. It wraps your data into frames, tags it with a MAC address (like a hardware name tag), and uses error detection mechanisms like checksums to identify corrupted transmissions. It also performs media access control i.e. it ensures that devices don’t all “talk” at once, which would cause network noise, thus acting as a moderator to determine how devices access and share the physical communication medium, helping prevent collisions and maintain orderly data flow. Analogy: Think of a traffic officer at a busy intersection, letting cars (data frames) move in turn, directing them to the right driveways (MAC addresses), and checking their license plates (checksums) for legitimacy.

- Physical Layer (Layer 1): Finally, we get to the bottom of the stack, the Physical Layer. This is the layer that handles the actual transmission of raw bits, 1s and 0s, over physical channels like Ethernet cables, fiber optics, or even Wi-Fi radio waves. This layer converts digital data from the Data Link Layer into electrical, optical, or electromagnetic signals, and vice versa on the receiving end. It defines how fast the bits are sent, what voltage levels mean “1” or “0”, and how those bits are physically encoded. It doesn’t know or care what the data means, it just makes sure it gets from one end to the other.

Layer Protcols

As we discussed earlier, in the OSI model, each layer communicates only with its peer layer on the other side – it’s like layers are having a long-distance conversation. But for these conversations to work, they need to speak the same language. That’s where protocols come in.

You can think of layer protocols as language contracts – agreed upon rules that ensure peer layers on different machines can understand each other and interpret messages correctly. Each layer uses its own protocol depending on its role:

- The Transport Layer might use TCP for reliable delivery or UDP for fast delivery

- The Network Layer uses IP to handle addressing and routing

- The Application Layer uses protocols like HTTP, SMTP, or DNS, depending on the task

Each protocol handles a specific part of the communication puzzle, ensuring that the data flows smoothly from one system to another, even across vast and complex networks.

Network Layer Protocols

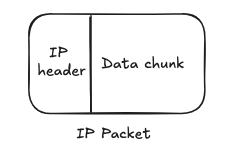

IP (Internet Protocol) dominates the Network layer of the OSI model. It’s job? Addressing and routing i.e. figuring out where your data needs to go and how to get it there.

IP breaks down the data segments coming from the Transport Layer (Layer 4) into smaller, manageable chunks called packets. Each packet is tagged with a source and destination using an IP header (typically 20-60 bytes), and then routed across the internet through multiple hops and networks. The IP header also contains a field called the Protocol Number, which helps the recipient machine identify whether the payload is TCP, UDP, ICMP, etc.

IP is focused solely on delivery. IP doesn’t concern itself with:

- What’s inside the packet

- Whether the packet gets there

- Whether it arrives in order

- Whether it’s corrupted or duplicated order

IP simply pushes the packet out the door and relies on Transport Layer protocols like TCP or UDP to fill in the gaps.

What’s an IP Address? An IP address is like a digital home address – it uniquely identifies a machine on a network so others know where to send data. When a machine connects to a network (either physically through cables or wirelessly through Wi-Fi), the machine sends a DHCP (Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol) request to ask the local router (which is the only device it can talk to at the moment) for an IP address. The router, acting as the DHCP server, keeps a list of available IP addresses and assigns one to the machine. The machine can then send and receive information over the network.

| Type | Visible on the Internet? | Used For | Assigned By |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public IP | Yes | Talking to the wider internet | Internet provider (ISP) |

| Private IP | No | Inside local networks (home, office) | Your router (via DHCP) |

Devices inside a private network (e.g., your laptop, phone, or smart TV) use private IPs. Your router uses a public IP to communicate with the internet on behalf of your entire local network.

There are 2 versions of IP addresses:

- IPv4: The older and still most widely used version. Example address:

192.168.0.1– it has 32 bits in total. Each number in the address (like192) is 8 bits, and there are 4 groups of them. This allows for about 4.3 billion unique IPv4 addresses, which can’t handle the exploding number of devices on the internet. - IPv6: The newer version designed to support the massive scale of the modern internet. It has 128 total bits – 128 bits are split into 8 groups, and each group is 16 bits. Exmaple address:

2001:0db8:85a3:0000:0000:8a2e:0370:7334

Transport Layer Protocols

This layer is dominated by 3 protocols: TCP, UDP, and QUIC. Depending on what guarantees you want, you can choose either of them to communicate with other machines.

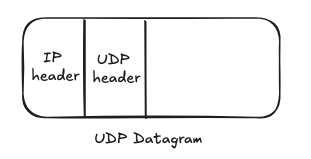

1. UDP (User Datagram Protocol) – Quick and Dirty Delivery Service

UDP (User Datagram Protocol) is one of the fundamental building blocks of network communication. It’s designed for speed and efficiency, but that performance comes with a trade-off: UDP is inherently unreliable.

When data comes from the application layer (Layers 5-7 of the OSI model), it’s encapsulated in a UDP datagram by adding a lightweight 8 Byte header.

- Source Port: Port of the sender (16 bits)

- Destination Port: Port of the receiver (16 bits). This tells the receiving machine which application (e.g., a web server or DNS resolver) the data should be delivered to. Example: Port 80 → HTTP server; Port 53 → DNS service

- Length: Length of the UDP datagram (16 bits)

- Checksum: Optional error checking for the datagram (16 bits)

These UDP datagrams are then sent directly without setting up a connection with the receiver – there’s no guarantee of delivery. Moreover, there are no acknowledgments and no retransmissions in this protcol i.e. If a datagram is lost, arrives corrupted, or shows up out of order, UDP won’t notice. It’s up to the application to implement any additional reliability, ordering, or error recovery, if needed.

Think of UDP like dropping a postcard in a mailbox: it’s fast and simple, but you don’t get a confirmation that it arrived, and it might not show up at all. It’s a connectionless and stateless protocol, making it extremely lightweight and ideal for certain use cases. UDP is a great fit when:

- Speed and low latency are more critical than perfect delivery

- You can tolerate some data loss

- You’re working with real-time or broadcast applications

Common use cases that rely on UDP under the hood or in niche ways:

- Streaming Media (Audio/Video): Real-time playback is more important than re-transmitting lost packets (e.g.,: Netflix, YouTube)

- VoIP (Voice over IP) and Video Conferencing: Speed is more important than perfection. It’s OK if a word or pixel drops here or there, as long as the conversation flows smoothly (e.g., Zoom, WhatsApp)

- DNS (Domain Name System): DNS queries are small and fast; retransmission can be handled by the application if needed

- Online Gaming: Fast reactions are key. It’s more important to get updates quickly than perfectly

- Sensor Networks and IoT devices: These devices don’t need perfect delivery but quick and light communication to save battery and power (e.g., A weather sensor in your garden)

- Log Shipping and Telemetry: Logs/metrics are typically fire-and-forget and tolerant to loss

- Video Surveillance Systems: Dropped frames are acceptable but delay is not

- One-to-many communication: Broadcasting and multicasting are easier with UDP because UDP is connectionless and doesn’t require a one-to-one relationship like TCP does (e.g., Finding Devices on a Network)

In short, UDP favors performance over precision - and in the right scenarios, that’s exactly what you need. If you’re sending important data (like emails or files), you’d want something more reliable, like TCP, which checks for errors and delivery.

2. TCP (Transmission Control Protocol) – Reliable but Fussy Courier Service

|

|---|

| TCP Connection Setup and Teardown Flow |

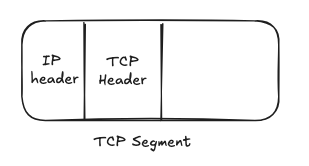

TCP is like sending a package with a tracking number and delivery confirmation – everything is accounted for, and nothing is left to chance. It’s a connection oriented protocol, meaning it establishes a reliable communication channel between sender and receiver before any data is transmitted.

To initiate this connection, TCP uses a three step handshake:

- The client sends a SYN (synchronize) message to the server – essentially saying, “Can you hear me?”

- The server replies with a SYN-ACK – “I hear you, Can you hear me?”

- The client responds with an ACK – “I hear you”

Once connected, TCP ensures reliable, ordered delivery through a number of built-in mechanisms. Every TCP segment that is sent is numbered (so it arrives in order), checked for damages (error checking), and confirmed when delivered (acknowledgement). If something is lost or corrupted, it is automatically re-sent.

Data from the application layer (Layers 5-7 of the OSI model) is encapsulated into TCP segments, each with a header that’s 20 to 60 bytes long. The header includes:

- Source and Destination Ports

- Sequence numbers: Indicate where this segment fits in the overall data stream

- Acknowledgment numbers: Confirms safe delivery of everything received so far and tells the sender exactly where to resume

- Checksum: Detects errors

- TCP flags: Indicate the segment’s role – starting (SYN), ending (FIN), acknowledging (ACK), etc

As you can see, the TCP header is more complex and bulky compared to UDP - but that complexity is what enables its reliability, ordering, and congestion-awareness. TCP also implements:

- Flow control: Prevents the sender from overwhelming the receiver. This is managed using a sliding window and the Window Size field in the TCP header, which tells the sender how much data the receiver is currently able to handle

- Congestion control: Even if the receiver can handle more, the network in between might be struggling. TCP watches for signs of congestion (like packet loss or delays) and slows down when needed

Ending a TCP connection is just as careful as starting one – think of it as a polite goodbye at the end of a phone call. It’s a four step process:

- The side initiating the close (e.g., the client) sends a FIN (finish) flag – “I’m done sending data and want to terminate this connection”

- The other side (e.g., the server) responds with an ACK - “Got it”

- The server might still be sending data. Once it’s finished sending data, it sends its own FIN

- The client replies with a final ACK, confirming the shutdown

TCP wants to make sure all data is safely delivered before closing the connection. That’s why it doesn’t just cut the cord but confirms that both sides are truly finished. Since TCP connections are persistent, one of the machines must explicitly initiate this connection teardown to end communication.

Everyday use cases that rely on TCP:

- Web browsing (HTTP/HTTPS): Reliable, ordered delivery of web pages and resources

- Emails (SMTP, IMAP): TCP ensures complete and correct delivery of messages

- File transfers (FTP, SFTP): Accuracy and reliability in transferring large files

- Remote access (SSH): TCP ensures secure and uninterrupted command-line sessions

- Software Updates and Package Managers: Tools like

apt,yum,pipuse TCP as it ensures files are downloaded completely and correctly - Even cybercriminals use TCP because it’s reliable and can be disguised as normal traffic (like HTTP)

3. QUIC – Fast & Secure Express [Optional Read]

If TCP is like a reliable delivery truck, QUIC (Quick UDP Internet Connections) is more like a smart, encrypted drone: it avoids traffic, flies straight to your window, and delivers multiple packages simultaneously. Developed by Google, QUIC reimagines how data moves across the internet, addressing two major limitations of traditional transport protocols:

- Slow start: Establishing a secure TCP connection involves multiple round trips between the client and server - first for the TCP handshake, then for TLS (Transport Layer Security, encrypts and secures the data). QUIC eliminates this delay by merging transport and encryption into a single handshake, dramatically speeding up connection times and boosting performance.

- Head-of-Line Blocking: TCP ensures in-order delivery, which means if an early packet (say, packet #1) is lost, the receiver has to wait for it to be retransmitted before it can process subsequent packets (like #2, #3, and so on). QUIC, the foundation of HTTP/3, avoids this bottleneck by supporting multiple independent streams. Think of it as a highway with several lanes: if one lane is blocked, traffic in the others keeps flowing. Lost packets only stall the specific stream they belonged to, not the entire connection.

By rethinking the fundamentals of transport layer communication, QUIC makes web browsing faster, more efficient, and more secure.

Sockets

Think of a socket as a doorway: applications use it to send and receive data, while the OS kernel does all the heavy lifting that happens beyond the door:

- Receiving and assembling IP packets

- Managing ports, maintaining connections, ensuring reliability, and more

In essence, sockets serve as an interface between user space applications and the kernel’s networking stack. They are virtual endpoints, that allow applications to connect, send, and receive data over the network, without having to deal directly with physical networking hardware or low-level protocols. It’s important to note that a socket isn’t a physical or hardware component; it’s entirely a software construct.

By abstracting away the complexities of underlying protocols like TCP, UDP, and IP, sockets offer developers a clean, standardized way to interact with the network. Each socket is uniquely identified by a combination of an IP address and a port number. When paired with a transport protocol (TCP or UDP), this forms a complete communication endpoint.

There’s no better way to truly understand how TCP and UDP work than by building them yourself. Check out these examples showing how to create simple TCP and UDP servers in Python using the standard socket library.

The deeper you go into networking, the more you appreciate the elegance behind every message, every stream, every click. In this post, we uncovered the foundational layers that make communication between machines possible, from sockets and transport protocols to IP addressing and the OSI model. These building blocks quietly power every interaction on the internet.

Thanks for hanging out and reading along. In the next post, we’ll move up the stack and explore the Application Layer, where all the user facing magic happens through protocols like HTTP.